Ready, Set, Ruby!

A few weekends ago, Spike went to SoCraTes, where he learned a game called Set. The premise of the game is fairly simple:

There are a certain number of cards laid out on the table from a deck of 81 total cards. Each card has four characteristics, and three possible options for each characteristic:

- Color - red, green, purple

- Shape - diamond, pill, squiggle

- Fill - solid, stripe, empty

- Number - one, two, three

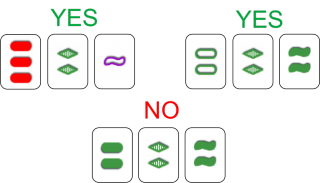

A complete ‘set’ consists of three cards that all have nothing in common, or all have exactly one trait in common. If two cards share a trait but not the third, it is not a set.

From the Warwick Maths Society

We got into a discussion about how many possible sets there were in a deck of 81 cards, if you were to lay out all 81 cards on a table and not remove any. We could have just googled it, but we thought it would be more interesting to try to conceptualize this problem and solve it with code.

This probably is not the most elegant approach (neither of us come from maths backgrounds), but as a first pass, I felt it was more important to try to solve the problem so we understand the domain, and strive for mathematical elegance and resource efficiency later. So, using Ruby as our weapon of choice, we set out to create every possible combination of triples, then sort through those combinations, selecting only the ones that are valid combinations.

1) Model the possibilities within each characteristic using arrays and symbols. To help prevent accidental mutation of these arrays, .freeze them. This potentially makes the approach a little less extensible, and I would probably never do this in a real application, but in this particular case, we know that the card characteristics won’t change within the domain of the problem.

class SetCards

NUMBERS = [1, 2, 3].freeze

COLOURS = [:red, :purple, :green].freeze

FILLS = [:solid, :stripe, :empty].freeze

SHAPES = [:diamond, :pill, :squiggle].freeze

end

2) Loop through these arrays one, within another, to generate a new array, containing all 81 cards represented as hashes.

def self.create_cards

NUMBERS.map do |number|

COLOURS.map do |colour|

FILLS.map do |fill|

SHAPES.map do |shape|

{

number: number,

colour: colour,

fill: fill,

shape: shape

}

end

end

end

end.flatten(3)

end

CARDS = create_cards.freeze

3) Next, we need to generate every possible 3-card combination. Fortunately, Ruby has a method for this!

def all_triples

CARDS.combination(3).to_a

end

Yes, it really is that easy. .combination is actually a method that belongs to the Enumerable module, but we need an array to be returned for data manipulation. For anyone who’s curious, there are 85,320 different triples.

4) Now that the triples are set up, we can begin to think about the trickier part: How do we pick out the triples that meet the criteria for being a valid combination?

If we revisit the rules of the game, the criteria is actually quite clear:

If two cards share a trait but not the third, it is not a set.

Say that this is our triple:

triple = [{ number: 3, colour: :red, fill: :solid, shape: :pill },

{ number: 3, colour: :purple, fill: :stripe, shape: :squiggle },

{ number: 2, colour: :green, fill: :empty, shape: :diamond }]

We know this isn’t a set, because the first and second cards share the number 3, but not the third. So if we had an array that collected together all of the values of the same key, called .uniq on it, and two elements remained, it is disqualified as a set.

To represent this in code, we could try something like this, as a first pass:

def valid_set?(triple)

numbers = []

triple.each do |card|

numbers << card[:number]

end

numbers.uniq.count != 2

end

However, this is really horrible because we’d actually need four times as much code to test every attribute. We could meta-program some of the repetition away, but the purpose of the method may then become unclear. The second problem is that a separate array is being set up inside the body of this method just to be manipulated. When this happens, it is usually a pretty good indication that there is a better way to do this.

5) If you’ve ever used Excel to build a pivot table, this Ruby method will feel very familiar to you: Ruby has a neat method called .transpose, which, when called on an array of arrays, takes the first element of every array and creates a new array, takes the second elements into a new array, and so on.

Before we do this, we actually need to replace the hashes with just the bits of information we’re interested in comparing – the values. Like so:

pry(main)> triple.map(&:values).transpose

=> [[3, 3, 2], [:red, :purple, :green], [:solid, :stripe, :empty], [:pill, :squiggle, :diamond]]

We could iterate through each of these new inner arrays now, and return as soon as we encounter a case where there’s an odd one out:

def valid_set?(triple)

triple.map(&:values).transpose.each do |attribute|

return if attribute.uniq.count == 2

end

end

Another possible implementation:

def valid_set?(triple)

triple.map(&:values).transpose.select do |attribute|

attribute.uniq.length == 2

end.empty?

end

The rspec tests for the first implementation run about 50% faster, because as soon as the method encounters the first non-valid set of attributes, it doesn’t bother to check the rest. With the second method, all attributes still have to be checked. But some developers may find the second implementation more readable.

- Putting it all together

All that remains now is to loop through all 85,320 triples. Something like this:

def count_valid_sets(all_selections)

all_selections.map do |selection|

valid_set?(selection)

end.count(true)

end

It seems like there’s a bit too much logic going on here, so we pulled out a named private method:

def count_valid_sets(all_selections)

valid_sets(all_selections).count(true)

end

private

def valid_sets(all_selections)

all_selections.map do |selection|

valid_set?(selection)

end

end

Lastly, recalling a piece of feedback that Katrina Owen had once left on an exercism.io kata that I had submitted ages back, writing concise code is not always the same as writing readable code. It is slightly unclear what .count(true) does, so if we map out a helpful symbol (and nils) rather than booleans:

def count_valid_sets(all_selections)

valid_sets(all_selections).count(:valid)

end

private

def valid_sets(all_selections)

all_selections.map do |selection|

:valid if valid_set?(selection)

end

end

The correct answer is 1,080 distinct possible sets. I really enjoyed this exercise, because it was never really about arriving at the number of 1,080 – rather, it was about learning to approach an initially complex problem in a disciplined, stepwise way. Ruby may not objectively be the best language for computation, but when you’re still learning to code, it is important to use whatever tool you feel the most comfortable with, so that you can focus on problem-solving rather than the mechanics of using the language.

On discussing this with Mateu from 8th Light (a shout-out to the whole London team, who are awesome), he suggested approaching the problem in reverse: Rather than generating every possible combination and filtering, we could be more discerning about what cards are generated in the first place. Our approach had the shape of a funnel – start large, then whittle down, whereas what he had in mind was the complete opposite: start small, and build up gradually.

If you would to take a crack at modeling Mateu’s method, throw it on Github and tweet at me - @deniseyu21 :-)